INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTICS

Start to Learn Linguistics is mainly taken from Todd, Loreto. 1987. An Introduction to Linguistics. York Press and it is also compiled from some linguistics sources to provide basic information about the analysis and description of languages and about the ways in which human beings use their languages to communicate with one another. That is what Start to Learn Linguistics about, and how it should be defined.

Start to Learn Linguistics is intended to serve as an introduction to linguistics to more advanced and more specialized material for those students who wish to continue the study of linguistics. It also provides a basic foundation in concepts and terminology for those students—particularly in education and the various service professions—who do not plan to be linguists but who feel that the ability to read linguistic literature related to their own field of expertise would be a useful skill. Finally, Start to Learn Linguistics is written for those who have no specific professional goals, but who are simply interested in the subject.

Chapter 1: WHAT IS LINGUISTICS?

What is Language?

The Component of Language

Chapter 2: PHONOLOGY

Phonetics

Phonetic Transcription

The organ of Speech

Vowel and Consonants

Articulation

Articulatory Setting

Classification of Consonants

Manner of Articulation

Place of Articulation

Classification of Vowel

The Cardinal Vowels

Suprasegmental Phonemes

Chapter 3: THE SOUNDS OF ENGLISH

The Phonemes of English

The Consonants of English

The Vowel of English

Consonant Clusters

Consonant Clusters in Initial Position

Consonant Clusters in Final Position

Chapter 4: MORPHOLOGY

Free and Bound Morphemes

Allomorphs

Derivational Morphology

Inflectional morphology

Inflection versus Derivation

Summary

Chapter 5: LEXICOLOGY

What do we mean by ‘word’?

Word Formation

Word Classes

Summary

Chapter 6: SYNTAX

The phrase

The clause

The sentence

Subordinate Clauses

Sentence Structure

Phrase Structure Tree

Summary

Chapter 7: SEMANTICS

The Meaning of ‘Meaning’

Polysemy

Synonymy

Antonymy

Hyponymy

Hipernymy

Meronymy

Ambiguity

Idioms

Summary

Chapter 8: BRANCHES OF LINGUISTICS

Sociolinguistics

Psycholinguistics

Applied Linguistics

Students’ Activities

Phonetic Spelling

References

What is Linguistics?

Linguistics is usually defined as ‘the scientific study of language. Such a statement, however, raises two further questions: what do we mean by ‘scientific’? and what do we mean by ‘language’? the first question can be answered relatively easily but the second needs to be examined more fully. When we say that a linguist aims to be scientific, we mean that he attempts to study language in much the same was as far as possible without prejudice. It means observing language use, forming hypotheses about it, testing these hypotheses and then refining that on the basis of the evidence collected. To get a simplified idea of what is meant, consider the following example. With regard to English, it might make a hypothesis that adjectives always precede nouns and support of this hypotheses, we could produce the following acceptable uses:

a good man

a dead tree

But against our hypothesis, we would find the following acceptable sentences:

The man is good.

The tree is dead.

Where our adjectives do not precede the nouns they modify, in addition, a careful study of the language would produce further samples such as:

life everlasting

mission impossible

As human beings, we all learn to speak at least one language because of this common ability, we tend to take this precious possession of language very much for granted. If we ask the man in the street what language is, he might say, “Oh, it is what we use in communication” or “It is made up of sounds when we speak” or “It is made up of words that refer to things”, or “It is made up of sentences that convey meaning.” Each of those statements contains a part of the truth, but as language teachers, our curiosity about language, the subject we teach, cannot be satisfied by such vague general statements or bits of unrelated information. Yes, language is used for communication, and it is made up of sounds. But what kinds of sounds and how are the sounds related to the words, the words to the sentences and the sentences to each other? We are interested in the relationships, because when we begin to see those relationships, we can understand how a language works.

WHAT IS LANGUAGE?

An important characteristic of language is recursion. This means sentences may be produced with other sentences inside them. This may be done, for example, by relativisation (the use of relative clauses): This is the boy that found the dog that chased the cat that … Another example of the process of recursion is conjunction (use of co-ordinating conjunctions) : Cheng went into the shop, (and he) asked for the manager, (and he) made a complaint, (and he) …

Also, language is arbitrary. The relation between a word and its meaning is a matter of convention: the animal called dog in English is called anjing in Malay and aso in Filipino. That is there is no necessary connection between the sounds people use and the objects to which these sounds refer. Also, we cannot tell before hand that the adjective occurs before the noun in English but after the noun in Vietnamese and Bahasa Malaysia, if we are unfamiliar with these languages. Words have the meaning they do and occur in the order they do, just because the native speakers of the language agree to accept them as such.

Language is a social phenomenon. It is a means of communication between individuals. It also brings them into relationship with their environment. Language is therefore socially learned behavior, a skill that is acquired as we grow up in society.

All languages are equally complex. Each language is part of the culture that produces it and is adequate for the needs of the people who use it. Any language, therefore, is as good as any other in that it serves the purposes of the particular culture. Words may be created or borrowed as the need arises. No language is intrinsically better or worse than any other.

How does the human language differ from animal language? Animals too communicate with one another. They bark, rattle, hoot, bleat, etc., and to some extent, these noises serve the same purposes as human language. One difference is that the animal system of communication can produce only a limited number of messages and animals cannot produce new combinations of noises to meet the needs of new situations, as human beings can. Also, no animal system of communication makes use of the dual structure of sound and meaning with its complex relationships that we study as grammar. Another important difference is that animal systems are genetically transmitted.

THE COMPONENT OF LANGUAGE

When a parrot utters words or phrases in our language, we understand them although it is reasonably safe to assume that the parrot does not. The parrot may be able to reproduce intelligible units from the spoken medium but has no awareness of the abstract system behind the medium. Similarly, if we hear a stream of sounds in a language we do not know, we recognize by the tone of voice whether the person is angry or annoyed but the exact meaning eludes us. To have mastery if a language, therefore, which are comprehensible to other users of the language, and in addition, being able to decipher the infinity of language patterns produced by other users of the language. It is thus a two-way process involving both production and reception.

As far as speech is concerned, the process involves associating sounds with meaning and meaning with sounds. With writing, on the other hand, language competence involves the association of a meaning (and sometimes sounds) with a sign, a visual symbol. Thus, our study of language will involve us in an appraisal of all of the following levels of language:

language

phonology – sounds

morphology – meaningful combinations of sounds

lexis – words

syntax – meaningful combination of words.

semantics – meaning

When we have examined these levels and the way they interact, we will have acquired the necessary tools to study languages in general (linguistics), the variety in language and the uses to which people put languages (sociolinguistics), the ways in which people teach and learn languages (applied linguistics) and the value of the study of language in understanding the human mind (psycholinguistics). W

PHONOLOGY

Phonology involves two studies: the study of the production, transmission and reception of speech sounds, a discipline known as ‘phonetics’, and the study of the sounds and sound patterns of a specific language, a discipline known as ‘phonemics’.

PHONETICS

When we speak we produce a stream of sound, which is extremely difficult to examine because it is continuous, rapid and soon gone. The linguist has therefore to find a way to break down the stream of speech so that the units may be studied and described accurately. In studying speech we divide these stream into small pieces that we call segments. The word ‘man’ is pronounced with a first segment [ m ], a second segment [ æ ] and a third segment [ n ]. it is not always easy to decide on the number of segments. To give a simple example, in the word ‘mine’ the first segment is [ m ] and the last is [ n ] , as in the word ‘man’ discussed above. But should we regard the [ ai ] in the middle as one segment or two? We will return to this question.

Human beings are capable of producing an infinite number of sounds but no language uses more than a small proportion of this infinite set and no two human languages make use of exactly the same set of sounds. When we speak, there is continuous movement of such organs as the tongue, the velum (soft palate), the lips and the lungs. We put spaces between individual words in the written medium but there are no similar spaces in speech. Words are linked together in speech and are normally perceived by one who does not know the language (or by a machine) as an uninterrupted stream of sound. We shall, metaphorically, slow the process down as we examine the organs of speech and the types of sound that result from using different organs.

PHONETIC TRANSCRIPTION

Linguists use a phonetic alphabet for the purpose of recording speech sounds in written or printed form. A phonetic alphabet is based on the principle of one letter per sound, so that people know which sound we are referring to when we use a certain letter. Such an alphabet provides a quick and accurate way of writing down the pronunciation of individual words and of showing how sounds are used in connected speech. It must be remembered, however, that a phonetic alphabet does not teach sounds, nor is it necessary to use phonetic transcription in teaching pronunciation.

Many systems of phonetic transcription have been invented. The International Phonetic Association (IPA) transcription represents British pronunciation, the discussion is based n the Received Pronunciation, (RP), while the Trager-Smith transcription represents American pronunciation.

Figure 1 shows the main organs of speech: the jaw, the lips, the teeth, the teeth ridge (usually called the alveolar ridge), the tongue, the hard palate, the soft palate (the velum), the uvula, the pharynx, the larynx and the vocal cords. The mobile organs are the lower jaw, the lips, the tongue, the velum, the uvula, the pharynx and the vocal cords and although it is possible to learn to move each of these at will, we have most control over the jaw, lips and tongue.

THE ORGANS OF SPEECH

Fig.1.1: The organs of Speech and English consonants

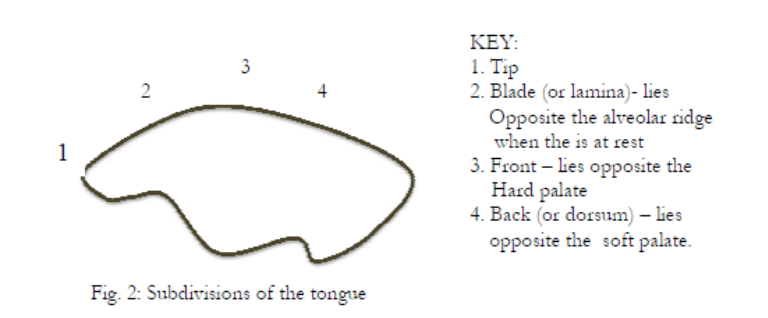

The tongue is so important in the production of speech sounds that, for ease of reference, it has been divided into four main areas, the tip, the blade (or lamina), the front and the back as shown in Fig. 2

Sounds could not occur without air. The air required for most sounds comes from the lungs and is thus aggressive (‘going out’). Certain sounds in languages can, however, be made with air sucked in through the mouth. Such sounds are called ingressive (‘going in’). The sound of disgust in English, a click often written ‘Tch!’, is made on an ingressive air stream. Coming from the lungs the air stream passes through the larynx, which is popularly referred to as the ‘Adam’s apple’. Inside the larynx are two folds of ligament and tissue which make up the vocal cords.

VOWEL AND CONSONANT

Sounds can be divided into two main types. A vowel is a sound that needs an open air passage in the mouth. The air passage can be modified in terms of shape with different mouth and tongue shapes producing different vowels. Consonant is formed when the air stream is restricted or stopped at some point between the vocal cords and the lips. The central sound in the word ‘cat’ is a vowel. The first and the third sounds are consonants. More will be said about vowels and consonants in the course of this chapter but these rough definitions will serve our purpose temporarily.

ARTICULATION

The sounds of speech can be studied in three different ways. Acoustics phonetics is the study of how speech sounds are transmitted. Auditory phonetics is the study of how speech sounds are heard. Articulatory phonetics is the study of how speech sounds are produced by the human apparatus. This approach in speech analysis is the one most useful for a language teacher, since he/she needs to know how individual sounds are made in order to help her students produce the desired sounds.

In the production of speech sounds, the organs in the upper part of the mouth may be described as places or points of articulation and those in the lower part of the mouth as articulators. When we produce speech sounds, the airflow is interfered with by the articulators in the lower part of the mouth. The resulting opening is called the manner of articulation of the speech sound.

ARTICULATORY SETTING

Just as each language uses a unique set of sounds from the total inventory of sounds capable of being made by humans, so to each group of speakers has a preferred pronunciation. In English, the most frequently used consonants are formed on or near the alveolar ridge; in French, the favored consonants are made against the teeth; whereas in India many sounds are made with the tip of the tongue curling towards the hard palate, thus producing the retroflex sounds so characteristic of Indian languages. The most frequently occurring sounds in a language help to determine the position of the jaw, tongue, lips and possibly even body stance when speaking. A speaker will always sound foreign in his or her pronunciation of a language if the articulatory setting of its native speakers has not been adopted.

CLASSIFICATION OF CONSONANTS

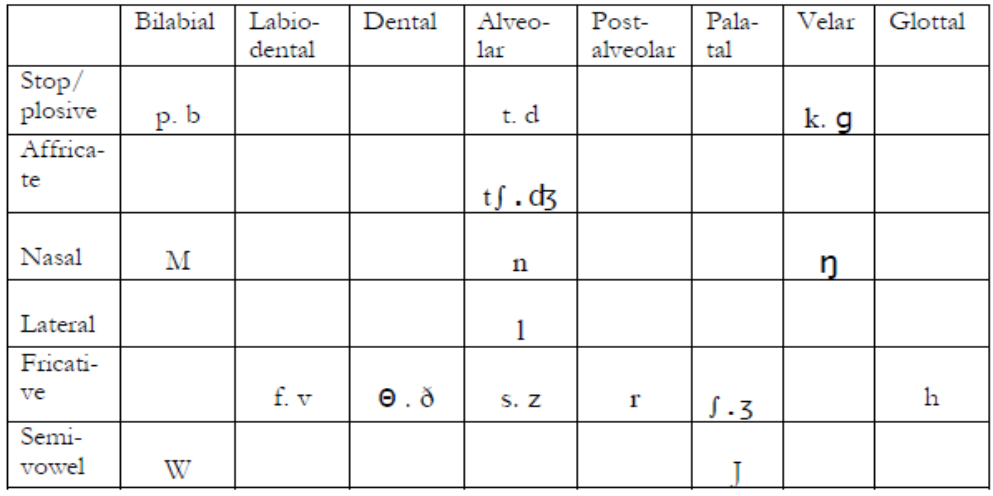

The answers to the four questions can tell us how the consonants are produced and also help us to classify or describe them.

- Are the vocal cords vibrating? The answer to this question tells us whether the sound is voiced or voiceless.

- What point of articulation is approached by the articulator? The answer gives the adjective in naming the consonant. For example, if the upper lip is approached by the lower lip, the sound is bilabial, e.g. [m, b]. If the upper teeth are approached by the lower lip, the sound is labiodental, e.g. [f, v].

- What is the manner of articulation? The answer supplies the noun in naming consonant, e.g. stops, fricatives, affricates.

- Is the air issuing through the mouth or nose? The answer tells us whether it is an oral or a nasal sound. This may be taken with (3) as another manner of articulation as it supplies another noun in the naming of consonants, i.e. nasal

We will group the consonant sounds of English according to their manner of articulation in the following discussion.

MANNER OF ARTICULATION

The ears can judge sounds very precisely, distinguishing the pure resonance of a tuning fork from the buzzing sound of a bee or the sharp report of a gun. More important for speech, perhaps, we can also distinguish between the voiceless sounds like ‘p’ and ‘t’ in ‘pat’ and the voiced sounds like ‘b’ and ‘d’ in ‘bad’ or between the voiceless ‘p’ in ‘pat’ and the nasal ‘m’ in ‘mat’. Speech exploits all these abilities and many more and scholars have devised ways of classifying sounds according to the way they are made.

The first obstacle the air meets in the vocal cords may be open, in which case the sound will be voiced. The vocal tract is resonance chamber and different sounds can be produced by changing the shape of the chamber. If you study the various types of closure below, it will help you to describe the different types of sound you can make.

Plosives: These involve complete closure at some point ion the mouth. Pressure builds up behind the closure and when the air is suddenly released a plosive is made. In English, three types of closure occur resulting in three sets of plosives /p/* and /b/; it can be made by the tongue pressing against the alveolar ridge, producing the alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/ and it can be made by the back of the tongue pressing against the soft palate, producing the velar plosives /k/ and /g/.

Fricatives: These sounds are the result of incomplete closure at some point in the mouth. The air escapes through a narrowed channel with audible friction. If you approximate the upper teeth to the lower lip and allow the air to escape you can produce the labio-dental fricatives /f/ and /v/. Again, if you approximate the tip of the tongue to the alveolar ridge, you can produce the alveolar fricatives /s/ and /z/.

Trills: These involve intermittent closure. Sounds can be produced by tapping the tongue repeatedly against a point of contact. If you roll the /r/ at the beginning of a word saying.

… r.r.r.roaming …

You are tapping the curled front of the tongue against the alveolar ridge producing a trill which is, for example, characteristic of some Scottish pronunciations of English.

Lateral: These sounds involve partial closure in the mouth. The air stream is blocked by the tip of the tongue but allowed to escape around the sides of the tongue. In English, the initial /l/ sound in ‘light’ is a lateral; so is the final sound in ‘full’.

Nasals: These sounds involve the complete closure of the mouth. The velum is lowered, diverting the air through the nose. In English, the vocal cords vibrate in the production of nasals and so English nasals are voiced. The three nasals in English are /m/ as in ‘mat’, /n/ as in ‘no’ and /ŋ/ as in ‘sing’.

Affricates: Affricates are a combination of sounds. Initially there is complete closure as for a plosive. This is then followed by a slow release with friction, as for fricative. The sound at the beginning of ‘chop’ is a voiceless affricate represented by the symbol /t∫/. We make the closure as for /t/ and then release the air slowly. The sound at the beginning and end of ‘judge’ is a voiced affricate, represented by the symbol /ʤ /.

Semi-vowels: The sounds that begin the words ‘you’ and ‘wet’ are made without closure in the mouth. To this extent, they are vowel-like. They normally occur at the beginning of a word or syllable; however, and thus behave functionally like consonants. The semi-vowels are represented by the symbols /j/ and /w/.

All sounds can be subdivided into continuants, that is, sounds which can be continued as long as one has breath: vowels, fricatives, laterals, trills, frictionless continuants; and non-continuants, that is, sounds which one cannot prolong: plosives, affricates and semi-vowels.

PLACE OF ARTICULATION

The eight commonest places of articulation are:

Bilabial: Where the lips come together as in the sounds /p/, /b/ and /m/

Labiodental: Where the lower lip and the upper teeth come together, as for the sounds /f/ and /v/.

Dental: Where the tip or the blade of the tongue comes in contact with the upper teeth as in the pronunciation of the initial sounds I ‘thief’ and ‘then’, represented by the symbols /θ/ and /ð/.

Alveolar: Where the tip or blade of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge which is directly behind the upper teeth. In English, the sounds made in the alveolar region predominate in the language. By this we mean that the most frequently occurring consonants /t, d, s, z, n, l, r/ are all made by approximating the tongue to the alveolar ridge.

Palato-alveolar: As the name suggests, there are two points of contact for these sounds. The tip of the tongues is close to the alveolar ridge while the front of the tongue is concave to the roof of the mouth. In English, there are four palato-alveolar sounds, the affricates /t∫/ and /ʤ / and the fricatives /∫/ and /ʒ /, the sounds that occur, respectively, at the beginning of the word ‘shut’ and in the middle of the word ‘measure’.

Palatal: For palatal sounds, the front of the tongue approximates to the hard palate. It is possible to have palatal plosives, fricatives, laterals and nasals, but in English the only palatal is the voiced semi-vowel /j/ s in ‘you’.

Velar: For velars, the back of the tongue approximates to the soft palate. As with other points of contact, several types of sound can be made here. In English there are four consonants made in the velar region, the plosives /k, g/ , the nasal /ŋ/ and the voiced semi-vowel /w/ as in ‘woo’.

Uvular, pharyngeal and glottal sounds occur frequently in world languages. They are not, however, significant in English and so will not be described in detail.

CLASSIFICATION OF VOWEL

Since vowels are produced with free passage of the air stream, they are less easy to describe and classify than consonants. The two articulatory organs to be considered are the tongue and lips for these two organs can mould and change the shape of the vocal tract by their movements in the production of vowels. It is the general shape of the vowel tract that gives the distinctive quality of sound of any vowel.

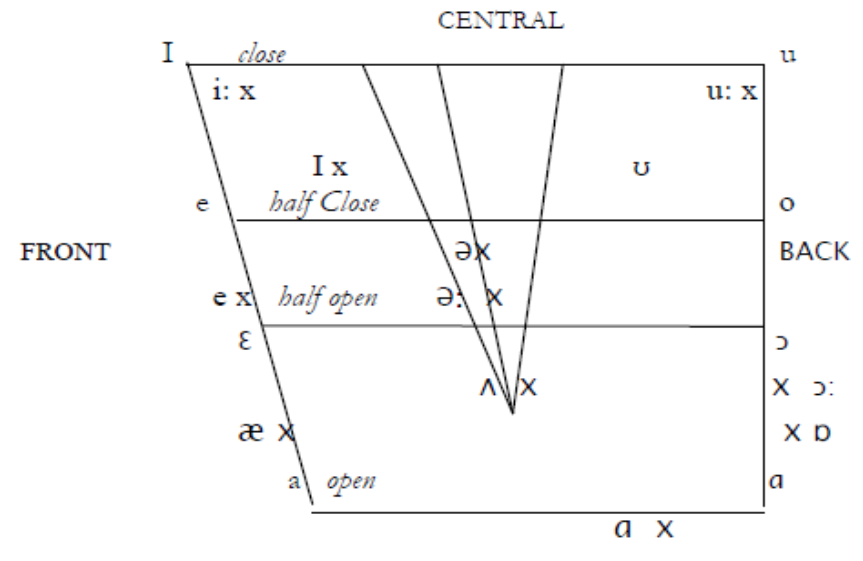

THE CARDINAL VOWELS

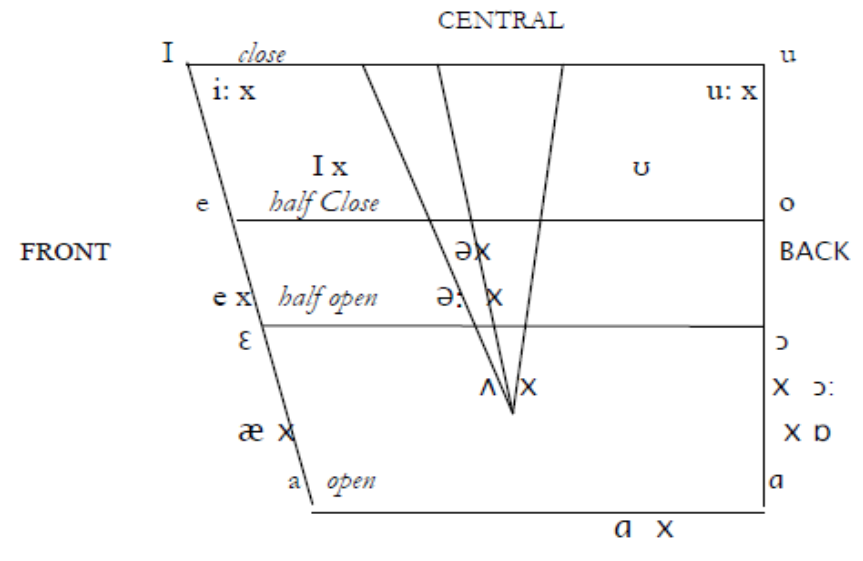

The symbols for these vowels and their placing on the vowel chart are shown in Figure 3. The vowels [i] and [ɑ] were chosen first as representing the closest front and the openest back vowel respectively. Then [e, Ɛ , a] were determined auditory to occupy positions at equal intervals from each other. The same procedure was used in choosing [ɒ, o, u]. These are eight vowels of fixed quality to which we can compare any new vowel. By listening to the cardinal vowel we can soon tell, for example, whether the new vowel is half-way between [i] and [e] or one-quarter of the way from [Ɛ] to [ɒ]. The vowels of English have been plotted on to the diagram in Figure 3 to show their relationship to the cardinal vowels.

Fig. 1.3 The cardinal vowels with the English vowels represented by crosses.

It may prove useful to offer a summary to guide the reader in the techniques to select in describing sounds. In describing a vowel it is important to state:

(1) the length of the vowel, that is, whether it is long or short.

(2) whether the vowel is oral or nasal* (*All English vowels are oral)

(3) the highest point of the tongue

(4) the degree of closeness

(5) the shape of the lips

Thus the vowel sound in ‘tree’ would be classified as a long, oral, front, close, unrounded vowel. The vowel in ‘doom’ would be a long, oral, back, close rounded vowel. It is well to remember that when the front of the tongue is raised towards the hard palate we have a front vowel. When the back of the tongue is raised towards the soft palate, we have a back vowel. If the centre of the tongue is raised towards the juncture between the hard and soft palates, then we have a central vowel. The vowel sound in the word ‘the’ is a central vowel and would be described as short, oral, central, half-open, with neutrally spread lips.

In describing consonants, one should state:

(1) the type of air stream used (in English all speech sounds are made on an egressive air stream although certain sounds of disgust and annoyance are made on an ingressive air stream)

(2) the position of the vocal cords (apart for voiceless sounds, approximated and vibrating for voiced sounds)

(3) the position of the velum (raised for oral sounds, lowered for nasal; that is, we must state whether a consonant is oral or nasal)

(4) the manner of articulation (for example plosive, fricative, and so on)

(5) the place of articulation (for example bilabial, alveolar and so on)

Thus, if we were asked to describe the initial sound in ‘buy’ and the final sound in ‘tin’ we would say that /b/ is made on an aggressive air stream and is voiced, oral, plosive and bilabial, and that /n/ is also uttered on an aggressive air stream and is voiced, nasal and alveolar.

SUPRASEGMENTAL PHONEMES

In addition to finding the consonant and vowel segments (the segmental phonemes), the linguist must also identify the suprasegmental phonemes used in a language system. They include things like pitch, stress, intonation and juncture. They are called “suprasegmental” because they can occur only with the segmental phonemes, they are imposed on the segmental phonemes. Basically, the method used is the same as that employed in looking for the segmental phonemes. That is, whether a certain feature contrasts with another and whether the contrasts exists in minimal pairs. The analysis of suprasegmental phonemes is more complicated that segmental phonemes and linguists tend to differ in their analysis.

PITCH differences may result in differences of meaning at the word level in the tone languages like Thai and Chinese, the height and/or direction (up-sown contrast level) of pitch can distinguish words. In Chinese, for example, there are four tones which can distinguish words. If you say / t∫u/ with a high level pitch it means “lord”. A beginner of Chinese may therefore wrongly say “I praise the pig”, when he means “I praise the lord”. Pitch is therefore phonemic in Chinese, because it can distinguish between pairs of words like the above.

STRESS is the degree of loudness given to some syllables in relation to others. The significance of stress at the word level can be illustrated by its use in English. Minimal pairs like the following show that stress is phonemic in English.

Phonemic Transcription Noun Verb

/insens/ incense incense

/pƏmit/ permit permit

/insʌlt/ insult insult

/ridʒekt/ reject reject

In the above pairs, it is the difference in stress that makes a difference in meaning.

It is usual to describe English as having four degrees of stress., but for the purpose of teaching English as second language there is a simpler analysis. According to this analysis, there are two kinds of stress: fixed stress and variable stress. Words of more than one syllable have fixed stress while monosyllabic words have variable stress.

THE SOUNDS OF ENGLISH

In the previous chapter, phonology has two aspects. We have dealt in general terms with the production, transmission and reception of sounds and we shall now turn our attention to the sound patterns in English. Since Standard English has no official pronunciation, we find considerable variation throughout the world: an American does not sound like an Australian and neither sounds like an Englishman. It would be impossible to cover all the variations found and so the description will be limited to the pronunciation sanctioned in Britain and in the U.S by radio and television what will be described, therefore, are the network norms established by BBC (National Broadcasting Company) and CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) in the United States.

PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY: WHAT ARE THEY?

PHONETICS and PHONOLOGY both study the sounds of speech but in somewhat different ways. Phonology is the study of sound systems in particular languages. It is concerned with significant units of sound called PHONEMES and the patterns or relationships between them. The symbol for that sound is enclosed in slash lines. For example the sound at the beginning of the English word tell is represented by the symbol /t/. this sound is a phoneme in English. It is significant because it can distinguish meaning. For example, the word tell is a different word from sell because the first word begins with the phoneme /t/ and the second begins with the phoneme /s/. they have different sounds and different meanings.

LETTERS, SOUNDS AND SYMBOLS

LETTERS are, of course, the symbol we use to make up the alphabet and to write words. They may be used to represent spoken sounds but they are not sounds. In fact, most writing systems do not represent the sounds of speech in an entirely accurate manner. This is particularly true in English. Think a moment about the fact that the vowel in sheep is spelt with ee; the vowel in meat is spelt ea; the vowel in piece is spelt with ie. And yet all three words contain the same vowel sound.

Phonetic SYMBOLS, unlike the letters with which we normally write, represent the sounds of speech in a one-to-one fashion: each symbol represents one sound and each sound is represented by one and only one symbol. For example, the sound which is spelt with th as in think is really only one sound and so there is one phonetic symbol for it: [ θ ]. On the other hand, the x in box represents two sounds. The phonetic symbols for these sounds are [ ks ].

THE PHONEMES OF ENGLISH

All human beings alike, yet every human being has a unique set of fingerprints. In a similar way, all languages make use of consonants and vowels yet no two languages have the same set of distinct sounds of phonemes. A phoneme is not one specific sound but it is like the common denominators of all realizations of a specific sound. Let us take an example. If we say the words:

pin spin nip

aloud, we realize that the ‘p’ sounds are all slightly different. The ‘p’ in ‘pin’ is pronounced with a lot of breath, the ‘p’ in ‘spin’ has qualities of the ‘b’ in ‘bin’ and the ‘p’ in ‘nip’ is pronounced as if it were followed by a short vowel. All these ‘p’ sounds are different and indeed no two people ever pronounce ‘p’ in exactly the same way, but the differences are not sufficiently great to be used to distinguish meanings in English. We say, therefore, that all the ‘p’ sounds in English belong to the same phoneme. If, on the other hand, we examine the words:

pin pen

we realize that although these words only differ in their vowel sounds they refer to distinct objects. Since these vowel sounds can be used to distinguish many words:

din den

kin ken

tin ten

we say that the vowels /I/ and /e/ are different phonemes.

THE CONSONANTS OF ENGLISH

One method of establishing the phonemes of a language is by means of minimal pairs. An illustration will help to explain this. In English, we have the word pan and the word ban. These words differ fairly fundamentally in meaning but, as far as the sounds go, they differ only in the initial segment. The sounds /p/ and /b/ can be shown to distinguish meaning in many pairs of words:

pet bet

pill bill

post boast

punk bunk

We can, therefore, conclude that /p/ and /b/ are distinct phonemes in English. The consonants of British and American English are essentially the same and twenty-four distinct consonants can be distinguished by means of minimal pairs. A list such as:

pie buy tie die guy fie vie lie

my nigh thigh thy sigh shy rye high

allows us to isolate the following consonant phonemes: /p, b, t, d, g, f, v, l, m, n, θ, ð , s, ∫ , r, h/

Lists such as:

chin sin win

gin tin

add / t∫, ʤ, w/, while:

simmer sinner singer

provide us with /ŋ / and:

rice rise

isolate /z/

The remaining three phonemes are revealed by three sets below:

leper letter ledger leisure

Which give us /ʒ / and:

car bar far

which provide /k/, and finally:

bard card yard

which reveal /j/.

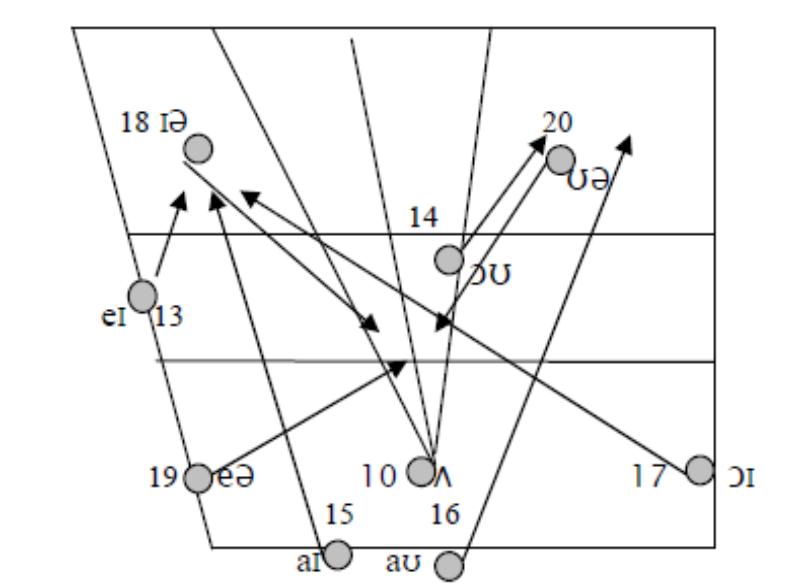

THE VOWEL OF ENGLISH

As might be expected, there is much greater variation in the pronunciation of vowel phonemes than is the case with consonants. The variety of British English that we have chosen to describe has twelve monophthongs and eight diphthongs whereas our US variety has ten monophthongs and five diphthongs. The systems will be described first of all, and then the differences will be accounted for. They can be described as follows:

VOWEL 1 which has the phonetic symbol / i: / is a close, long, front vowel, made with spread lips. It occurs in such words as ‘eat’, ‘seed’ and ‘see’.

VOWEL 2 which has the phonetic symbol / I / differs from vowel 1 in both quality and length. It is a half-close, short, front vowel made with spread lips. It is also one of the most frequently used vowels in the English language and one that is often replaced by vowel 1 in the speech of non-native speakers. This vowel occurs in such words as ’it’, ‘sit’ and ‘city’.

VOWEL 3 which has the phonetic symbol / e / is a short, front vowel produced with spread lips. It occurs in words like ‘egg’ and ‘get’ but does not occur in word-final position in English.

VOWEL 4 which is represented phonetically by / æ / is a short, front, open vowel. It is made with the lips in a neutrally open position. It occurs in words like ‘add’, ‘sat’ and, like / e /, does not occur in word-final position in English.

VOWEL 5 is represented by the symbol / ɑ: /. It is a long, open, back vowel made with slightly rounded lips. It occurs in words like ‘art, ‘father’ and ‘far. This vowel does not occur in US English.

VOWEL 6 is represented by the symbol / ɒ /. This is a short, open, back vowel made in British English with slightly rounded lips and in the US with neutrally open lips. It is found in words such as ‘on’ and ‘pod’ and does not occur in word-final position. In US English words such as ‘card’ and ‘cod’ are distinguished by length of vowel and by the pronunciation of ‘r’ in the former rather than by any intrinsic difference in vowel quality.

Fig. 4: The positions of the twelve monophthongs in British English. (the vowels are based on the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, 2000)

VOWEL 7 is represented by / ɔ: /. This is a long, half-open, back vowel pronounced with lip-rounding. Again, there is more lip-rounding in the British pronunciation of / ɔ: /. This sound occurs in ‘all’, sawed’ and ‘raw’.

VOWEL 8 is represented phonetically by /ʊ/. This is a short, half-close, back vowel pronounced with lip-rounding. It does not occur in word-initial position but is found in ‘put’ and in ‘to’.

VOWEL 9 is transcribed / u: /. This is a long, close, back vowel produced with lip-rounding. It is found in words such as ‘’ooze’, booed’ and ‘too’.

VOWEL 10 is represented by / ʌ /. This is a short, open, centralized vowel. It does not occur in word-final position but is found in ‘up’ and ‘bud’.

VOWEL 11 does not occur in US English. It is represented by the symbol / ɜ: /. It is a long, central vowel and occurs in such words as ‘err’, ‘church’ and ‘sir’.

Fig. 5: Diphthongs in BBC English.

VOWEL 12 is represented by / Ə / and is the only vowel sound in English with a name. / Ə / is called ’schwa’. The schwa is the most frequently occurring vowel sound in colloquial English speech, and all unstressed English vowels tend to be realized as / Ə /. This is a short, central vowel which occurs in the unstressed syllables of such words as ‘ago’ and ‘mother’.

All the vowels described above are monophthongs. This means that there is no tongue movement during the production of the vowel sound. A diphthong, however, involves the movement of the tongue from one vowel position another.

VOWEL 13 is represented by /eI/. Like all English diphthongs it is long. It starts close to Vowel / e / and moves towards Vowel 2. This sounds occurs in such words as ‘ail’, ‘rain’ and ‘day’.

VOWEL 14 is represented by /Əʊ /. It starts near the centre of the mouth in British English and moves towards Vowel 8. This diphthong is narrower and is pronounced with more lip-rounding in US English. It occurs in such words s ‘oat’, ‘known’ and ‘go’.

VOWEL 15 is represented by / aI /. This is a wide diphthong which starts in the region of Vowel 4 and moves towards Vowel 2. This diphthong is found in words such as ‘aisle’, ‘fight’ and ‘high’.

VOWEL 16 is represented by /aʊ /. This is a wide diphthong which starts in the region of Vowel 4 and moves towards Vowel 8. It occurs in such words as ‘out’, ‘house’ and ‘now’.

VOWEL 17 is represented by / ɔI /. This diphthong begins in the region of Vowel 7 and moves towards Vowel 2. It occurs in such words as ‘oil’, ‘toyed’ and ‘boy’.

The above are the five diphthongs shared by British and US English.

VOWEL 18 is represented by / IƏ /. It is a centering vowel in that it starts near Vowel 2 and moves towards Vowel 12. This diphthong is found in such words as ‘ear’, ‘pierce’ and ‘beer’. You will notice that this diphthong occurs in words which involve post-vocalic ‘r’. The sound in such words would be represented by /ir/ in US English.

VOWEL 19 is represented by / eƏ /. It is a centering diphthong which starts near Vowel 3 and moves towards Vowel 12. It is found in such words as ‘air’, ‘paired’ and ‘there’. This sound is usually represented in US English by /er/, that is, by the combination of a vowel similar in quality to Vowel 3 followed by the consonant /r/.

VOWEL 20 is represented by / ʊƏ / (/ʊr/ in the US). It is a centering vowel starting near Vowel 8 and moving towards Vowel 12. This diphthong does not occur in word-initial position but is found in words like ‘tour’ and ‘moor’. With many speakers this diphthong is replaced by the monophthong /ɔ/ so that it is not uncommon to have speakers who pronounce ‘Shaw’, ‘shore’ and ‘sure’ in exactly the same way, as /ɔ/.

CONSONANT CLUSTERS

The English language permits a number of consonant clusters such as /dr/ and /spl/. There are restrictions on the type of combination which can occur. These can be summarized in two groups: consonant clusters in initial position, and consonant clusters in final position.

CONSONANT CLUSTERS IN INITIAL POSITION

The maximum cluster of consonants (C) in an initial position in English is three, and they must be followed by a vowel (V), thus: CCCV. If there are three consonants, however, the first must be /s/, the second must come from the set /p,t,k/, and the third must come from the set /l,r,w,j/, but these can only occur in certain patterns, as shown bellow:

The maximum cluster of consonants (C) in an initial position in English is three, and they must be followed by a vowel (V), thus: CCCV. If there are three consonants, however, the first must be /s/, the second must come from the set /p,t,k/, and the third must come from the set /l,r,w,j/, but these can only occur in certain patterns, as shown bellow:

The above possibilities are illustrated by the following words:

splash, sprain, spurious/spjʊƏriƏs/

strain, stew /stju:/

screech, sclerosis, squander /skwɔndƏ/ and skew /skju:/

If there are only two consonants in the cluster, the first must come from set /p,t,k,b,g,f,v,θ,s,∫,h/ in the following patterns. The normal orthography is used but the reader is reminded that sounds and not spellings are referred to:

CONSONANT CLUSTERS IN FINAL POSITION

English permits up to four consonants in word final position, so we have CCCVCCCC as a possible English word. Such words are uncommon but ‘strengths’ illustrates the patter. The following types of clusters can be established, starting with VCC:

The VCCC patter is quite frequent in English although it is not found as widely in the language as the VCC pattern.

pts as in scripts /skrıpts/

pst as in lapsed /læpst/

pθs as in depths /depθs/

tst as in blitzed /blıtst/

kst as in next /nekst/

mps as in limps /lımps/

ŋst as in amongst /Əmʌŋst/

etc.

The VCCCC pattern, where four consonants occur at the end of a word or syllable is rare in English and is only found when the inflectional endings /s/ and /t/ are added to a VCCC form as in ‘thousandths’ /θaʊzƏntθs/, exempts /eksempts/ or glimpsed /glimpst/.

SUMMARY

In this chapter, methods of describing the sound system of English have been examined. Each model of grammar has its own preferences and so different descriptions will emphasize different aspects of phonology. The account given above, however, is compatible with all models of grammar for English and will be extended in subsequent chapters where some of the most influential descriptions of English produced in the last fifty years are examined.